By Kevin Burls, Endangered Species Conservation Biologist

It’s no secret that water brings life to the desert. In Nevada, mountain streams and desert springs support plants and animals both common and rare, including insects and other invertebrates. These springs and streams can support diverse insect communities in the middle of what feels like very inhospitable habitat, often a hundred miles or more from any sizeable town. I spend a lot of time chasing western butterflies, and it’s no surprise to find yourself searching along a streambed or meadow edge in a remote mountain range. Most people I talk to are not shocked to hear there are butterflies in the far reaches of Nevada. But fireflies? That surprises almost everyone.

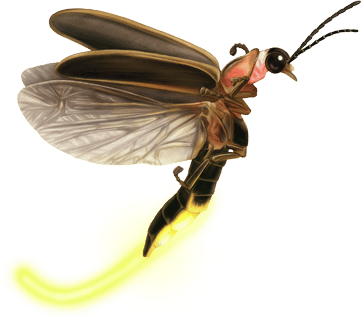

It’s true, there are fireflies in Nevada! However, our knowledge of fireflies here, including where they are, is very limited; there are currently only a handful of verified observations. This past July, I was lucky enough to survey for fireflies with my wife in some of our favorite parts of beautiful and wild eastern Nevada. Our first stop was Great Basin National Park at the north end of the Snake Range in far eastern White Pine County (and one of the United States’ least visited national parks). The park is most well-known for Lehmann Caves, and for another attraction in the dark: stargazing. In addition to the wonderful stars, we were also able to document the marsh flicker firefly, Pyractomena dispersa, localized around wet meadows and springs. The ample snowmelt and unique geology make this region exceptionally wet with numerous year-round springs even in the height of summer, supporting the snails and slugs on which the firefly feeds. Surveying here was a family affair: we were joined by our friends Josh, Heather, Kevin and Amber, and their kids, and all 8 of us were able to stand in front of a meadow at dusk, watching the males begin to flash from the ground, then later flying up several feet into the air for four quick flashes. Females responded from the ground, and we were able to take photos of both sexes. To say we were excited was an understatement- this was only my second firefly observation in Nevada!

From Great Basin National Park Cynthia and I traveled south to spots in Lincoln County, in southeast Nevada (but still 200 miles from the metropolis of Las Vegas). In a region with volcanic tuff geology springs again find their way to the surface in large numbers in the valleys, creating lush oases surrounded by white and pink rock outcrops. Not only were we successful in finding a large P. dispersa population enjoying the wet meadows, we also had the chance to meet and talk with a local state park ranger, Jordan, who was an accommodating and knowledgeable host. One of the great joys of fieldwork for me is making these connections with the people who work and live near our state parks, public lands and natural landscapes. These individuals are often the only full-time advocates these isolated animal populations have, are the only ones around to observe how they respond to disturbances, or are even the sole witnesses to population changes through the seasons. As with much of the fieldwork I do, we were only lucky enough to get a brief snapshot of the population.

With a long drive ahead of us, we were up early the next morning to head back to the Reno area. We would pass through one more potential firefly location, stopping only to note the habitat and admire the expansive meadows. I am excited to return to this region for more surveys in the future; there are almost certainly more firefly populations to be discovered. The Firefly Atlas provides an opportunity for all of us to contribute to a growing body of knowledge about the distribution of these special beetles and be advocates for fireflies, including species like Pyractomena dispersa that rely on isolated and fragile spring habitats and have many possible undiscovered locations. Observations reported to the Atlas are also shared with other programs like the Western Firefly Project, which seeks to learn more about flashing fireflies in the West. The collective action of community members across our respective states is a powerful tool in learning about and conserving these jewels of the desert night.