On a rainy evening in late May, I find myself squelching through the mud of a floodplain in northeast Georgia, soaking my pants from the wet grass as I get in place for nightfall. Most people would probably avoid going into a marsh at night on an early summer evening, but I am on a mission. I am searching for a whimsically named lightning bug that few people have heard of and even fewer have looked for.

In mid-June 1986 Dr. Jim Lloyd, a renowned firefly scientist, encountered a type of lightning bug he had never seen. While exploring a roadside wetland in Pickens County, South Carolina he found a small, dark-winged Photuris that looked identical to Photuris tremulans, but gave a distinctive rising and falling flash-train. He was struck by the consistency of this new firefly– it never switched patterns, unlike other Photuris fireflies that showed a complex repertoire of flickers and flashes. It was clearly different from any firefly he had seen before. Three days later, Lloyd returned to find that the valley bottom had been bulldozed to build a golf course. Lloyd referred to the firefly as Photuris F in his writings, and during his firefly wanderings throughout the southeast, he never found another population.

Long exposure photographs of loopy five flashes. Radim Schreiber/Firefly Experience.

It would be another 26 years before the species was noticed by scientists, this time on the other side of the Appalachians. Lynn Faust, a self-taught lightning bug expert, spotted an eccentric pattern of flashes in a Tennessee marsh in 2010 and nicknamed these beetles “loopy fives” for their erratic, up-and-down pattern of 5-7 flashes. She proceeded to study the population for years, getting to know its nightly and annual rhythms and the subtleties of its flash behavior. Faust knew that the body morphology and flash pattern of loopy five matched what Lloyd had seen in South Carolina, but it wasn’t until 2018 that Jim Lloyd finally assigned a scientific name to Photuris F and loopy five: Photuris forresti. That same year, Faust made a trip to South Carolina, confirming that loopy fives had not returned to Lloyd’s original site and discovering a different population about twelve miles to the south.

Tennessee and South Carolina were the only two states known to harbor loopy fives until 2021, when a landowner in Walton County, Georgia realized that he had snappy single sync fireflies (Photuris frontalis) on his property and became curious about the other species he might have. When he reached out to Lynn Faust, she suggested also checking the property for loopy fives, and when he surveyed the inlet of his small pond, he found them. Just four sites in three states over a period of more than 30 years. Could there be more?

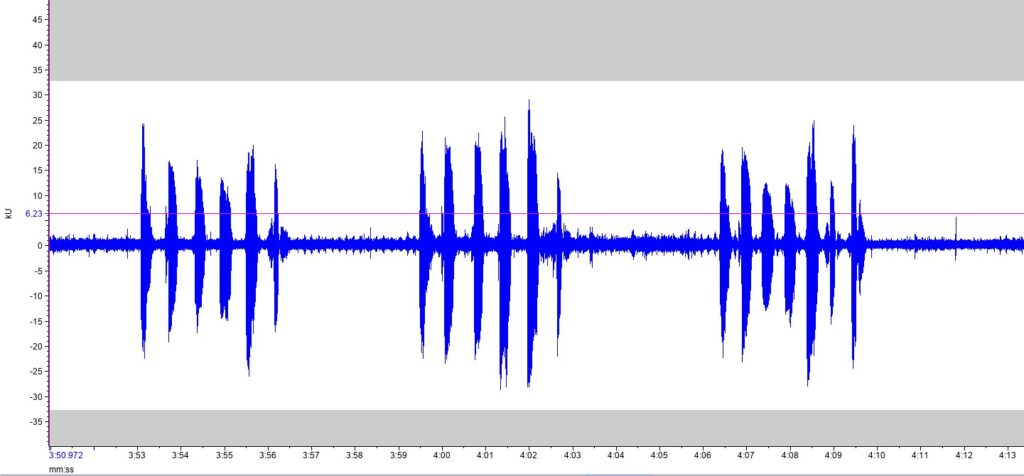

Back in the Georgia marsh, not far from Walton County, Georgia, my eyes adjust to the darkness as tree frogs and cricket frogs begin their raucous chorus. At 9:05 PM, I see the first flashes over the marsh, like a greenish campfire spark that rapidly blinks as it rises and then falls. “Loopy fives!” I start my voice recorder and fix my gaze on the wetland. “One. Two. Three. Four. Five. Six. Seven.” Then dark. It’s hard not to hold my breath as I wait for the next flash pattern. About ten feet from the first, another series of flashes begins. “One. Two. Three. Four. Five.” My voice and focus are tested as I strive to match the timing of the flashes, roughly transcribing light into sound over about three seconds.

After noting details about the air temperature and flash pattern measurements, I swing my net and catch a male loopy five, who lights up in alarm. I take photos of the firefly’s upper side and underside, confirming that it is indeed in the Photuris genus and not a cattail flash-train firefly (Photinus consimilis), who overlaps in habitat and has a similar flash pattern. A minute later, the loopy five flies back into the darkness, ready to continue its bobbing display.

Findings like this — a new population of a rarely reported species — are exciting. Yet that excitement is tempered by concern for the species, which was categorized as Endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species earlier this year. Even without knowing the precise boundaries of its range in the southern Appalachian Piedmont and Valley and Ridge, we know the future of Photuris forresti is threatened. Wetland loss, habitat degradation and fragmentation, encroaching light pollution, reduced water quality from urban development, and an increasingly unpredictable and extreme climate all increase this species’ extinction risk.

Are there more populations out there, that have just gone unnoticed? The season for finding loopy fives is narrow. Adults emerge as early as mid-May and disappear by the end of June, with nightly displays lasting for about three weeks at any one site. To better understand the distribution and status of this species, we need many more firefly seekers venturing into the night and out to the marshes.

Interested in helping with the search for loopy fives?

If you live in the Piedmont or Valley and Ridge regions of southern Appalachia (Alabama, Georgia, Tennessee, South Carolina, North Carolina) and own, manage, or have access to marshy wetlands, consider joining the search! Here’s how to get started.

To learn more about Photuris forresti

Faust, L. F. (2017). Fireflies, Glow-worms, and Lightning Bugs: Identification and Natural History of the Fireflies of the Eastern and Central United States and Canada. University of Georgia Press.

Lloyd, J. E. (2018). A Naturalist’s Long Walk Among Shadows; of North American Photuris: Patterns, Outlines, Silhouettes… Echoes. Bridgen Press. p.179-182.

Anna Walker (New Mexico Biopark Society, New Mexico), & Lynn Faust (Emory River Land Company). (2021). IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Photuris forresti. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Lynn Faust, Allen Grubbs, David Eargle, Carol Sanchez, Kate Mowbray, Austen Attaway, Kevin Conley, Russell Hardy, Chris Sermons, Gordon Ward, Rob Tiffin, and Bob and Mary Anne Inglis for facilitating and participating in loopy five survey efforts during the 2022 firefly season.